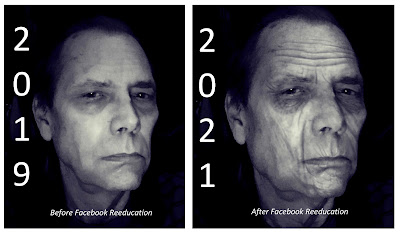

A Short Story… Because I still can, even after reeducation

1.0 or Out

He still had Harris tweeds and cowboy boots with boot chains. This was a definite comedown. Before, he’d been a music consultant at Borders, but he’d had to quit. The new boss was explaining the ropes.

“We are business telemarketing. Not the kind that wakes you up on the couch on an afternoon. We have a real product. It’s your job to sell them the free first issues and explain that after a month the subscription kicks in. Here’s the script you use.”

It was bullshit, of course. No thinking businessperson is going to sign on to an open-ended liability based on a random call from an uncredentialed caller.

“All you have to do is sell one prospect per hour, and you’re golden with us.”

One per hour.

“Can you do that?”

“Sure. But can I see what I’m selling?”

“Of course.” He was handed a sample copy and the selling script.

Then they entered the boiler room. Half a dozen black women with computer screens and headphones on. They didn’t turn around to see. Newcomers were not news. They were all talking up a storm. He could hear the script words flying.

The supervisor gave him a seat and a headset at a computer console on the long table with simple instructions. “The phone will ring in your headset and then you start reading the script. Got it? Take the order, hit enter, and the next prospect will be on the line.”

“Yes.”

He sat down, listened through the headset, the phone rang, distantly, and a voice from the bottom of a well said, “Jones here. How can I help you?” Jones? Are we really all anonymous in this enterprise?

He started reading from the script. “I’m calling from Landmark Publishing, Inc. We’d like to send you a free copy of our latest newsletter, which covers leading edge developments in the canning industry. Ways to save you time and mon—“ Which is when he hung up the phone.

The supervisor was gone. Now he was being welcomed by the other telemarketers. The one most in his face told him her name was “Rollie” and reassured him.

“It’s nothing personal,” she said. “They all get called multiple times. It’s our job to make ourselves different, professional, businesslike and helpful.”

Rollie was missing her two front teeth. But she sounded like an accountant. Her bubbly friend, name of Laverne, tried to make his CRT console homey. They were all wearing sweats. Others, including a white woman, patted his back and he reflexively protected his wallet.

He took another call, even deeper in the well than before. “I can’t hear,” he said.

Rollie found him another headset. Laverne promised to make sure he would have it always if it worked.

The new headset did work. Which began the first ritual.

Weeks followed. He drove his battered pickup truck to the Vineland boiler room every day. He took his cue from Rollie, who departed from the script only at the beginning, claiming she was returning a call. After which, he threw out the script altogether and just started winging it. Which got him to 2.0+ per day.

The supervisor had a meeting every mornIng. He played the most successful calls of the day before. But never the calls of the 2.0+ guy. They weren’t on script.

How did the women react to the old white guy with the tweeds, the boot chains, and the expensive watch? By this time they had all become buddies. He and Laverne took their smoke breaks together. By now he had learned that you didn’t really know anybody’s name. The phone would ring, mid-session, and a name would be called out, answered by someone you knew as someone altogether else. It didn’t matter. Buddies. Laverne had bruises on bare arms and even her throat. She had a habit of falling down, she said. What do you do. He did nothing.

One day, the white woman tried to heist his headset before he got in. Rollie and Laverne had a word with her before he arrived. His headset was in place awaiting him. He got 2.5 that day.

Lost his expensive watch at one point. A pin fell out of the bracelet. Found the pin, not the watch. A young black girl, new hire, gave him his watch back. What was going on?

Then came a holiday. Maybe Independence Day. Lots of food came in. Even the supervisor overlooked it. They all wanted the tweed 2.0 man to decide whose was best. He couldn’t decide. They were all the best he’d ever had. They all forgave him his indecision.

There followed a decline. He struggled to make 1.5. There was no censure. The supervisor wanted the women to keep following the script.

But he—he—couldn’t follow the script anymore. Not even his own.

Before telemarketing there had been Border’s Bookstore. He’d quit because his knees gave out. But not really. He’d quit because he saw Emily. He wasn’t supposed to be a cashier at a bookstore. He was supposed to be somebody. Then the day after Christmas he was a cashier and there she was,. The last time he’d seen her she was making a joke about middle-aged women’s boobs. “If you can put a pencil under them and the pencil doesn’t move, they’re definitely saggin’,” she said.

She hadn’t recognized him. But he lost his boot chain cool. Almost immediately. So he quit, left, never said goodbye. Should have said goodbye. They were friends. And he left all wrong.

Then did it all over again in the telemarketing circle. He had learned how to quit and run.

Later, he told me about it:

“What do you do? I remember the fact that I never knew their real names. They never really trusted me enough to tell me. They lied to me about who was beating them. They lied to me about the drugs they were doing. They lied to me about everything.

“Except they protected my headset and wanted me to like their potato salad best. Why, like every white guy I’ve ever known, I still feel guilty.

“I thought about it a lot. Then I figured it out. They used to gather round me, abandoning their constant whirring phone ringers, and they got off on me with some man or woman on the hook. Why they liked the White Guy after all. He was payback. They never copied what I did. I was getting into white people heads, and they looooved it. I sold the suckers a bill of goods, two per hour+, and that’s worth the price in potato salad.

“My guilt is absolved.”

Unless it isn’t and can never be.

Comments

Post a Comment